A Brief History of X-ray Telescopes

Marjorie Townsend and Bruno Rossi discuss the UHURU satellite's performance during preflight tests. UHURU was the first satellite dedicated solely X-ray astronomy. (Credit: NASA)

X-ray telescopes were first used for astronomy to observe the Sun, which was the only source in the sky bright enough in X-rays for those early telescopes to detect. Because the Sun is so bright in X-rays, early X-ray telescopes could use a small focusing element and the X-rays would be detected with photographic film. The first X-ray picture of the Sun from a rocket-borne telescope was taken by John V. Lindsay of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and collaborators in 1963. The first orbiting X-ray telescope flew on Skylab in the early 1970s and recorded more than 35,000 full-disk images of the Sun over a 9-month period.

Astronomers had to wait before using X-ray mirrors to detect extra-solar X-rays. This was because the right detectors needed to be developed first. X-ray astronomy required electronic detectors that were highly sensitive to light and able to pinpoint an X-ray photon on the detector. The first such detectors were the imaging proportional counter and the microchannel plate detector. Subsequently, more sensitive detectors were developed for X-ray astronomy, including CCD spectrometers and imaging gas scintillation proportional counters.

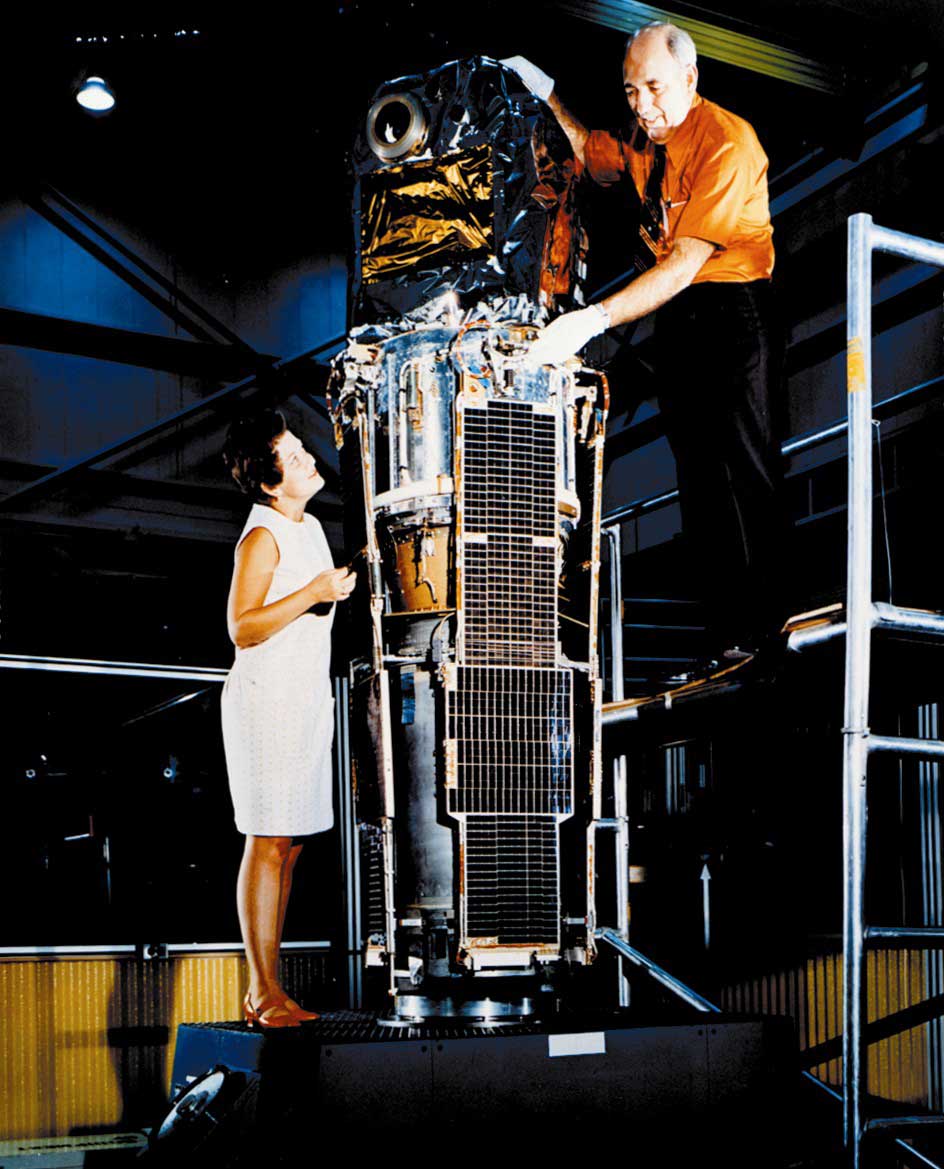

As with the solar observations, the first observations using X-ray imaging systems were done from sounding rockets. The first successful X-ray image of an extra-solar object was of the Virgo cluster of galaxies by Paul Gorenstein and collaborators in 1975. The inaugural use of Wolter optics for extra-solar astronomy was done by Saul Rappaport of MIT and his collaborators in 1977. Over the course of two rocket flights, they obtained the first true images of supernova remnants. Their image is shown below, alongside images taken later by a dedicated X-ray astronomy satellite.

The Cygnus Loop Supernova Remnant in X-rays as imaged by three different X-ray telescopes. From the left: image by early X-ray telescopes mounted on sounding rockets, image by the ROSAT's High Resolution Imager (HRI) instrument, image by the ROSAT's Position Sensitive Proportional Counter (PSPC) instrument. (Credits: rocket image: Rappaport et al, ApJ (1979) 227, 285; ROSAT images: N. Levenson (Johns Hopkins), S. Snowden (USRA/GSFC))

Major advances in imaging, and in X-ray astronomy in general, came with the launch of the first orbiting X-ray telescope, the Einstein Observatory, in 1978. Einstein demonstrated the ubiquity of X-ray emission from all classes of objects and revealed for the first time the structure of extended objects such as nearby galaxies and supernova remnants. Since then, many other imagers have been placed into orbit. Other early missions that carried imagers are EXOSAT, ROSAT, and ASCA.

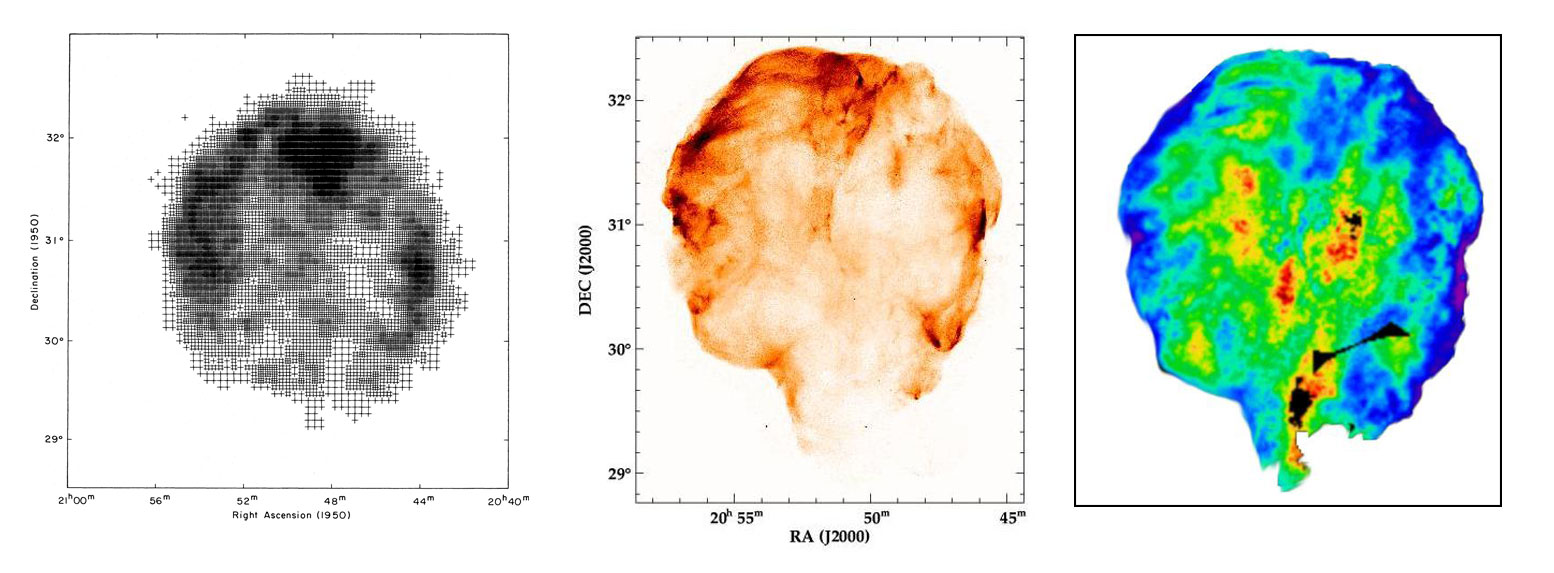

The next step in the evolution of X-ray telescopes was NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, launched in 1999. Chandra's resolution is about 50 times superior to that of ROSAT, providing astronomers with images of much higher quality and revealing more details than previously available. In fact, Chandra's mirrors are the highest quality X-ray mirrors made &150; an accomplishment even that is even more astonishing when considering the nested design required for X-ray observation.

Chandra's orbit is very eccentric, and takes it about 1/3 of the distance to the lunar orbit before returning closer to Earth. This odd orbit makes it possible for the observatory to obtain long exposures of targets without the interruption of Earth eclipsing the target, which happens during a typical, more circular orbit closer to Earth.

The Crab Nebula as imaged by ROSAT (left) and Chandra (right). (Credit: Credit: S. L.Snowden USRA, NASA/GSFC (ROSAT), NASA/CXC/SAO/F.Seward et al. (Chandra) )

Other current X-ray telescopes carry imagers, including XMM-Newton and NuSTAR. And astronomers look forward to further advances in X-ray astronomy with future missions.

Text updated: September 2018