Deriving Kepler's Formula for Binary Stars

Your astronomy book goes through a detailed derivation of the equation to find the mass of a star in a binary system. But first, it says, you need to derive Kepler's Third Law.

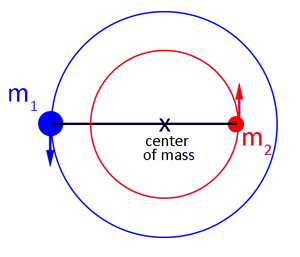

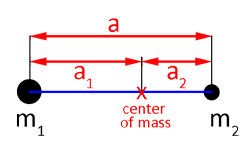

Consider two bodies in circular orbits about each other, with masses m1 and m2 and separated by a distance, a. The diagram below, shows the two bodies at their maximum separation. The distance between the center of mass and m1 is a1 and between the center of mass and m2 is a1.

Diagram showing two bodies in circular orbits about their center of mass.

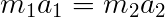

The center of mass is defined by:

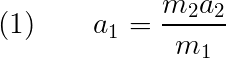

Which can be solved for a1:

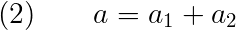

And, the total separation can be written as:

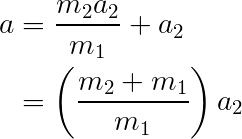

Using Equation (1) in Equation (2) gives

Or, solving for a2:

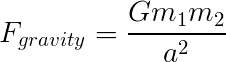

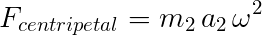

Now, set that aside for a moment and look at the forces working on m2. The forces acting on the mass are the gravitational force and centripetal acceleration from its orbital motion.

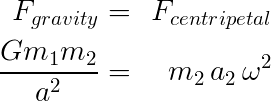

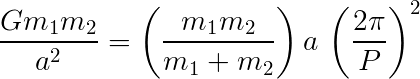

where G is the gravitational constant and ω is the angular acceleration. Equating these gives:

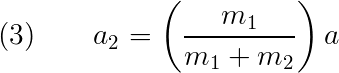

Now, using Equation (3) to substitute for a2 gives:

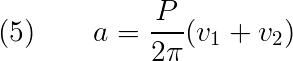

We can replace ω using the fact that P=2π/ω by definition. So,

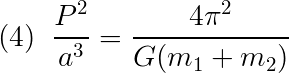

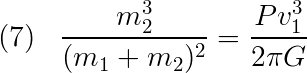

Canceling, rearranging, and gathering the unknowns to the left side of the equation gives Kepler's Third Law.

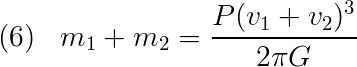

For a distant binary system, it is be difficult to determine the separation of the two stars in the binary system, a. However, using spectroscopy, it might be possible to find the velocity of one or both of the stars in the system.

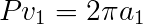

If we assume a circular orbit, we know that:

and

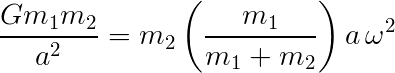

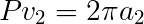

Using those, in Equation (2):

Then substituting Equation (5) in Equation (4),

![(P^2)/[(P/2pi) (v1+v2)]^3 = 4 pi^2 /[G (m1+m2)]](images/derive_binaryEqn4.png)

Rearranging and canceling gives:

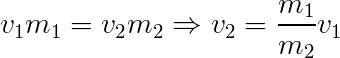

If we could see both stars in the binary system, this equation would work fine. However, there are times when we can only see one – for example, if there is a star in orbit with a black hole. For a circular orbit, we have:

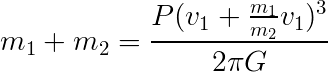

Replacing this for v2 in Equation (6) gives:

Gathering the masses to one side gives:

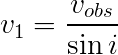

One last thing about the velocity in this equation. When we observe a system, it is usually at an angle with respect to us. That means that we need to account for that in the above equation. The observed velocity is related to by orbital velocity by:

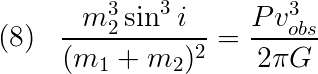

where vobs is the observed velocity and i is the angle of inclination of the system with respect to us. Substituting this into Equation (7), we finally get:

Whew. (Your textbook didn't say, "whew", but it could have!)

Now you are ready to use this equation.