Imagine the Universe News - 25 July 2006

Scientists Find Infant Solar System Awash in Carbon

| 25 July 2006 |

|

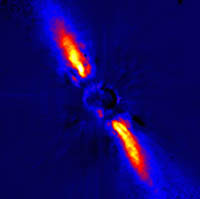

| This image of the circumstellar disk around Beta Pictoris shows (in false colors) the light reflected by dust around the young star at infrared wavelengths. (Credit: Jean-Luc Beuzit, et al. Grenoble Observatory, European Southern Observatory) |

Scientists using NASA's Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer, or FUSE, have discovered abundant amounts of carbon gas in a dusty disk surrounding a well-studied young star named Beta Pictoris.

The star and its emerging solar system are less than 20 million years old, and planets may have already formed. The abundance of carbon gas in the remaining debris disk indicates that the star's planets could be exotic, carbon-rich worlds of graphite and methane. Or conversely, the scientists say, Beta Pictoris and its environs might resemble our own solar system in its early days.

A team led by Dr. Aki Roberge of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., presents the FUSE observation in the June 8 issue of Nature. The new measurements make Beta Pictoris the first disk of its kind whose gas has been comprehensively studied. The discovery settles a long-standing scientific mystery about how the gas has lingered in this debris disk yet raises new questions about the development of solar systems.

"There is much, much more carbon gas than anyone expected," said Roberge, a NASA Postdoctoral Fellow and lead author on the Nature report. "Could this be what our own solar system looked like when it was young? Are we seeing the making of exotic, new worlds? Either prospect is fascinating."

Beta Pictoris, about 60 light years away, is 1.8 times more massive than our sun. This young star's disk was discovered in 1984. Earlier observations have hinted that a Jupiter-like planet may have already formed in this disk and that rocky terrestrial planets may be forming. Such planets would be too small and faint to observe with current instruments.

|

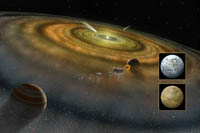

Artist's conception of the dust and gas disk surrounding the star Beta Pictoris. The inset panels show two possible outcomes for mature terrestrial planets around Beta Pic. The top one is a water-rich planet similar to the Earth; the bottom one is a carbon-rich planet, with a smoggy, methane-rich atmosphere similar to that of Titan, a moon of Saturn. (Credit: NASA/FUSE/Lynette Cook) |

The carbon gas detected by FUSE comes from unseen asteroids or comets orbiting the star. These collide with each other, releasing material in a process similar to how NASA's Deep Impact probe liberated dust and gas from within comet Tempel 1 last year.

The terrestrial planets in our solar system---Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars---formed from the collision of smaller planetary bodies such as asteroids about 5 billion years ago. During the few hundred million years after Earth was formed, asteroids and comets might have smashed into our planet to deliver virtually all of the water and organic material we see today. These materials are the building blocks of life on Earth.

Asteroids and comets orbiting Beta Pictoris might contain large amounts of carbon-rich material, such as graphite and methane. Planets forming from or impacted by such bodies would be very different from those in our solar system and might have methane-rich atmospheres, like Titan, a moon of Saturn.

"We have learned in the past ten years is that our galaxy is filled with other solar systems, and each one is different from the next," said Dr. Marc Kuchner of NASA Goddard, an expert on extra-solar planets. "If carbon-rich worlds are forming in Beta Pictoris, they might be covered with tar and smog, with mountains made of giant diamonds. Life on such a planet is not implausible, but it certainly would be exotic."

A second possibility is that Beta Pictoris might be similar to our solar system long ago. While local asteroids and comets don't seem carbon-rich today, some research suggests that certain meteorites called enstatite chondrite meteorites formed in a carbon-rich environment, and some scientists speculate that Jupiter has a carbon core.

"We might be observing processes that occurred early in our solar system's development," said Nature co-author Dr. Alycia Weinberger of the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

The mere presence of gas in the Beta Pictoris disk has been a mystery. Theoretical models predict that intense light from the young star should rapidly blow the gas away. The overabundance of carbon gas, discovered now for the first time, solves this mystery. Carbon has special properties that keep the gas in orbit around the star.

Other co-authors on the report are Dr. Paul Feldman, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore; and Drs. Magali Deleuil and Jean-Claude Bouret, Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille in France. The FUSE project is a NASA Explorer mission developed in cooperation with the French and Canadian space agencies by Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore; University of Colorado, Boulder; and University of California, Berkeley. NASA Goddard manages the program for NASA's Science Mission Directorate.