Black Holes

(Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center/J. Schnittman, J. Krolik (JHU) and S. Noble (RIT))

The simplest definition of a black hole is an object that is so dense that not even light can escape its surface. But how does that happen?

The concept of a black hole can be understood by thinking about how fast something needs to move to escape the gravity of another object – this is called the escape velocity. Formally, escape velocity is the speed an object must attain to "break free" of the gravitational attraction of another body.

There are two things that affect the escape velocity – the mass of object and the distance to the center of that object. For example, a rocket must accelerate to 11.2 km/s in order to escape Earth's gravity. If, instead, that rocket was on a planet with the same mass as Earth but half the diameter, the escape velocity would be 15.8 km/s. Even though the mass is the same, the escape velocity is greater, because the object is smaller (and more dense).

What if we made the size of the object even smaller? If we squished the Earth's mass into a sphere with a radius of 9 mm, the escape velocity would be the speed of light. Just a wee-bit smaller, and the escape velocity is greater than the speed of light. But the speed of light is the cosmic speed limit, so it would be impossible to escape that tiny sphere, if you got close enough.

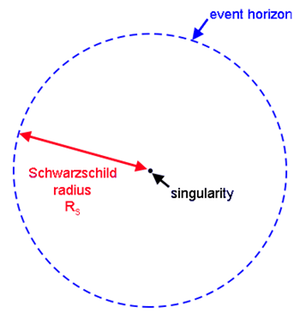

The radius at which a mass has an escape velocity equal to the speed of light is called the Schwarzschild radius. Any object that is smaller than its Schwarzschild radius is a black hole – in other words, anything with an escape velocity greater than the speed of light is a black hole. For something the mass of our sun would need to be squeezed into a volume with a radius of about 3 km.

(Credit: NASA's Imagine the Universe)

Structure of a black hole

There are two basic parts to a black hole: the singularity and the event horizon.

The event horizon is the "point of no return" around the black hole. It is not a physical surface, but a sphere surrounding the black hole that marks where the escape velocity is equal to the speed of light. Its radius is the Schwarzschild radius mentioned earlier.

One thing about the event horizon: once matter is inside it, that matter will fall to the center. With such strong gravity, the matter squishes to just a point – a tiny, tiny volume with a crazy-big density. That point is called the singularity. It is vanishingly small, so it has essentially an infinite density. It's likely that the laws of physics break down at the singularity. Scientists are actively engaged in research to better understand what happens at these singularities, as well as how to develop a full theory that better describes what happens at the center of a black hole.

Seeing the unseen

If light can't escape a black hole, how can we see black holes?

Astronomers don't exactly see black holes directly. Instead, astronomers observe the presence of a black hole by its effect on its surroundings. A black hole, by itself out in the middle of our galaxy would be very difficult to detect.

Imagine you arrive home one night to find the kitchen a mess. You know that it was clean when you left, but now there are dirty dishes in the sink and crumbs strewn about the counter. From the evidence, you know someone used the kitchen while you were out – in fact, you can even say that they made a sandwich and chips because of the types of crumbs you see on the counter. You might even be able to identify who in your household was in the kitchen based on what kind of chips they had or what they put on their sandwich. You never saw that person in the kitchen, but their effect on the kitchen was evident.

Studying black holes relies heavily on indirect detection. Astronomers cannot observe black holes directly, but see behaviors in other objects that can only be explained by the presence of a very large and dense object nearby. The effects can include materials getting pulled into the black hole, accretion disks forming around the black hole, or stars orbiting a massive but unseen object.

Credit: NASA GSFC/CI Lab

Types of black holes

Traditionally, astronomers have talked about two basic classes of black hole – those with masses about 5-20 times that of the sun, which are called stellar-mass black holes, and those with masses millions to billions times that of the sun, which are called supermassive black holes. What about the gap between stellar mass and supermassive black holes? For a long time astronomers had proposed a third class, called intermediate mass black holes, but it was just in the past decade or so that they have started finding possible evidence of this class of black hole.

Stellar-mass black holes are formed when a massive star runs out of fuel and collapses. They are found scattered throughout the galaxy, in the same places where we find stars, since they began their lives as stars. Some stellar-mass black holes started their lives as part of a binary star system, and the way the black hole affects its companion and their environment can be a clue to astronomers about their presence.

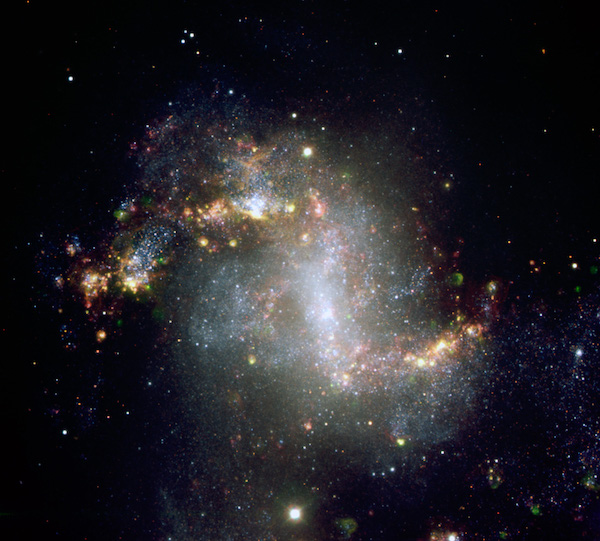

Supermassive black holes are found at the center of nearly every large galaxy. Exactly how supermassive black holes form is an active area of research for astronomers. Recent studies have shown that the size of the black hole is correlated with the size of the galaxy, so that the there must be some connection between the formation of the black hole and the galaxy.

With only a few candidate intermediate black holes, astronomers are just beginning to study them in any detail. These studies are complicated by the fact that many of the objects that initially looked like strong intermediate black hole candidates can be explained in other ways. For example, there is a class of object called ultraluminous X-ray sources (ULXs). These objects emit more X-ray light than known stellar processes. One model postulated that ULXs harbor an intermediate black hole; however, further study of these objects has favored alternate models for most of them. Stay tuned as astronomers work to unravel the mysteries of these elusive objects.

(Credit: ESO)

Updated: November 2016

Additional Links

- Quiz me about this topic!

- Cool fact about this topic!

- Try This !

- FAQs on Black Holes

- Give me additional resources!

Related Topics

- Supernovae

- X-ray Binaries

- Active Galaxies

- The Hole Story? New Type of Black Hole Poses Challenges

- Chandra Discovers the History of Black Hole X-ray Jets

- Scientists Observe Light Fighting to Escape Black Hole's Pull

- Black Holes May Take Space For a Spin

- ASD Podcast Featuring X-rays and Black Holes