Electromagnetic Spectrum

The Electromagnetic Spectrum

As it was explained in the Introductory Article on the Electromagnetic Spectrum, electromagnetic radiation can be described as a stream of photons, each traveling in a wave-like pattern, carrying energy and moving at the speed of light. In that section, it was pointed out that the only difference between radio waves, visible light and gamma rays is the energy of the photons. Radio waves have photons with the lowest energies. Microwaves have a little more energy than radio waves. Infrared has still more, followed by visible, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays.

The amount of energy a photon has can cause it to behave more like a wave, or more like a particle. This is called the "wave-particle duality" of light. It is important to understand that we are not talking about a difference in what light is, but in how it behaves. Low energy photons (such as radio photons) behave more like waves, while higher energy photons (such as X-rays) behave more like particles.

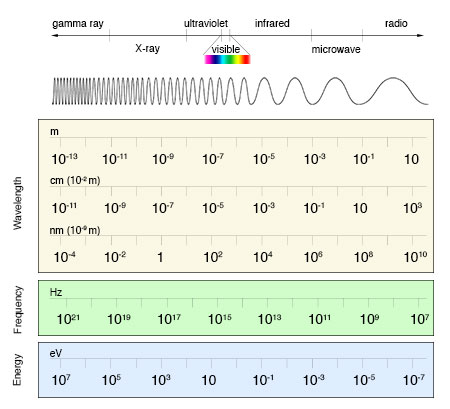

The electromagnetic spectrum can be expressed in terms of energy, wavelength or frequency. Each way of thinking about the EM spectrum is related to the others in a precise mathematical way. Scientists represent wavelength and frequency by the Greek letters lambda (λ) and nu (ν). Using those symbols, the relationships between energy, wavelength and frequency can be written as wavelength equals the speed of light divided by the frequency, or

and energy equals Planck's constant times the frequency, or

Where:

- λ is the wavelength

- ν is the frequency

- E is the energy

- c is the speed of light, c = 299,792,458 m/s (186,212 miles/second)

- h is Planck's constant, h = 6.626 x 10-27 erg-seconds

Conversion between wavelength, frequency and energy for the electromagnetic spectrum. (Credit: NASA's Imagine the Universe.)

![]() Show a

chart of the wavelength, frequency, and energy regimes

of the spectrum

Show a

chart of the wavelength, frequency, and energy regimes

of the spectrum

Astronomy Across the Electromagnetic Spectrum

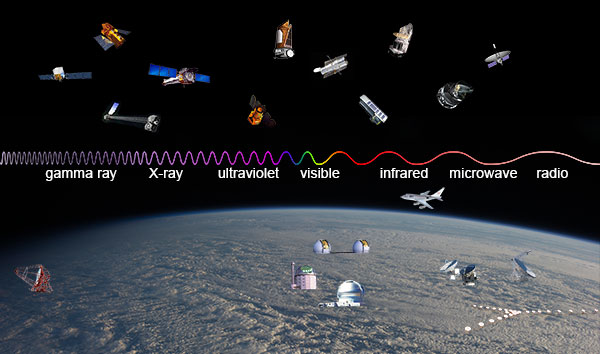

While all light across the electromagnetic spectrum is fundamentally the same thing, the way that astronomers observe light depends on the portion of the spectrum they wish to study.

For example, different detectors are sensitive to different wavelengths of light. In addition, not all light can get through the Earth's atmosphere, so for some wavelengths we have to use telescopes aboard satellites. Even the way we collect the light can change depending on the wavelength. Astronomers must have a number of different telescopes and detectors to study the light from celestial objects across the electromagnetic spectrum.

A sample of telescopes (operating as of February 2013) operating at wavelengths across the electromagnetic spectrum. Observatories are placed above or below the portion of the EM spectrum that their primary instrument(s) observe.

The represented observatories are: HESS, Fermi and Swift for gamma-ray, NuSTAR and Chandra for X-ray, GALEX for ultraviolet, Kepler, Hubble, Keck (I and II), SALT, and Gemini (South) for visible, Spitzer, Herschel, and Sofia for infrared, Planck and CARMA for microwave, Spektr-R, Greenbank, and VLA for radio. Click here to see this image with the observatories labeled.

(Credit: Credit: Observatory images from NASA, ESA (Herschel and Planck), Lavochkin Association (Specktr-R), HESS Collaboration (HESS), Salt Foundation (SALT), Rick Peterson/WMKO (Keck), Germini Observatory/AURA (Gemini), CARMA team (CARMA), and NRAO/AUI (Greenbank and VLA); background image from NASA)

![]() Learn more

about how astronomers

detect light from space across the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Learn more

about how astronomers

detect light from space across the entire electromagnetic spectrum.