Major Step Toward Knowing Origin of Cosmic Rays

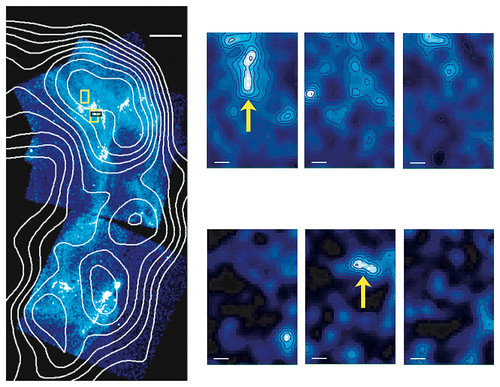

Recent observations from NASA and Japanese X-ray observatories have helped clarify one of the long-standing mysteries in astronomy – the origin of cosmic rays.

Outer space is a vast shooting gallery of cosmic rays. Discovered in 1912, cosmic rays are not actually rays at all; they are subatomic particles and ions (such as protons and electrons) that zip through space in all directions at near-light speed, with energies tens of thousands of times greater than particles produced in Earth's largest particle accelerators. Cosmic rays incessantly bombard Earth, smashing into the atoms and molecules high up in the atmosphere, and producing cascades of secondary particles that reach the surface.

Since the 1960s scientists have pointed to supernova remnants – the tattered, gaseous remains of supernovae – as the breeding ground of most cosmic rays. These remnants expand into the surrounding interstellar gas, an energetic interaction that produces a shock front containing magnetic fields that can accelerate charged particles to enormous energies, producing cosmic rays.

According to theory, charged subatomic particles bounce like pinballs around the shock front. They pick up speed until they move nearly the speed of light. Last year, observations from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory suggested that electrons are being accelerated rapidly (as fast as theory allows) to high energies in the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A.

Credit: CXC/Yasunobu Uchiyama/HESS/Nature