Fool-Proofing Galactic "Candles"

In this article, the Cosmic Times threads of distances in the Universe and supernovae come together as we discover that one type of supernovae, Type 1a supernovae, can be used as standard candles. The idea of standard candles comes up in nearly every edition of the Cosmic Times because the importance of standard candles in astronomy cannot be overemphasized – they are essential for determining distances to objects in the Universe.

Type 1a Supernovae

The last two editions of Cosmic Times have introduced the idea of supernova and different types of supernovae explosions. We know that supernovae are essentially exploding stars; however, there are two primary types of supernovae – those from a star at the end of its life and those from a white dwarf exceeding its critical mass. This latter type of supernovae, called Type 1a supernovae, is the type that we're interested in here.

A low-mass star (one with less than about 10 times the mass of our Sun) ends rather quietly when it exhausts its supply of material for nuclear fusion. Without nuclear fusion to hold the core up against gravity, the core collapses into a white dwarf. A white dwarf is held up against gravity by what is called "electron degeneracy pressure". There is a limit, however, to the amount of mass that electron degeneracy pressure can hold against gravity – 1.4 solar masses. When a white dwarf exceeds 1.4 solar masses, it will explode in a Type 1a supernova.

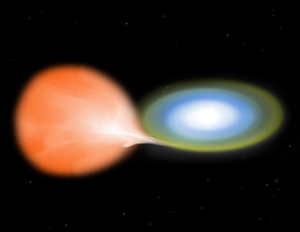

In general, a white dwarf all by itself in space will not gain mass very quickly. However, when a white dwarf is in a binary system, its companion may donate mass through two different mechanisms. If the white dwarf's companion is a massive star, it might put off a strong stellar wind (like our Sun's solar wind, but much stronger). Some of that stellar wind will be picked up by the white dwarf. A faster method for the white dwarf gaining mass is if its companion is a low-mass star that becomes a red giant star. If the two stars are close enough, the red giant may become "too big for its britches" and lose some of its outer layers of mass to the white dwarf (see image below).

Artist's impression of a binary star system with a white dwarf and a low-mass companion that has become a red giant. The red giant "donates" mass to the white dwarf. If the white dwarf's mass exceeds 1.4 solar masses, it will collapse and explode as a Type 1a supernova. (Image Credit: CXC/M.Weiss)

Type 1a Supernovae as Standard Candles

No matter what the mechanism that causes a white dwarf to gain mass, once it exceeds 1.4 solar masses, it will explode in a Type 1a supernova. Because they all explode at approximately the same mass, the explosions should be pretty much the same, no matter where they occur in the Universe. This is why astronomers can use Type 1a supernovae as standard candles. Type 1a supernovae are quite bright, so they can be observed at very large distances – much further distances than Cepheid variables, opening up more of the Universe for detailed study.

This article discusses a correction to the standard candle scale for slight differences in Type 1a supernovae. These differences might arise because the progenitor white dwarfs have different abundances of materials, or perhaps their surrounding environments are different. Either way, astronomers have determined a correction that accounts for the differences and re-calibrates the Type 1a distance scale. This sets up Type 1a supernovae for their important return in the 2006 Cosmic Times, where they become critical in the discovery of dark energy.

Other resources

The following webpages have more detailed information: